Beyond the scrap heaps of memory

As a man once said who is since deceased,

ugliness is beauty

that cannot be contained within the soul.

From the poem “As a Sheet of Ice Covers Granite” (1997) by Boris Ryzhy

“Gerlach’s farm is like a raindrop that reflects the world”, Dutch documentary film maker Aliona van der Horst (b. Moscow, 1970) recently said in an interview about her latest film (co-directed with Luuk Bouwman) GERLACH.

Her works contain many such raindrops. Small mirrors for big stories. Multifaceted reflections on the complexities of the universes around us. Take Gerlach. The title character ominously has been called the last farmer. Under the smoke of Dutch airport Schiphol, his farmland has slowly become constrained on all sides by intersections and roundabouts, distribution centers and gas stations. As a silent protest against the over-towering golden arches of the neon M of an American fast-food multinational nearby, Gerlach has erected a wooden G, as an advertisement for the potatoes he sells from his barn. Good for French fries too.

GERLACH is probably Van der Horst most narrative yet observational documentary. We follow the farmer through the seasons, entering the last term of his life. Not only his farm is being threatened, but so is his health, by rheumatism. When GERLACH was awarded the prize for best Dutch film during the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in 2023 the jury perceived the film in a global perspective and recognized themes of land expropriation and exploitation of the earth through intensive and industrial agriculture. There are other major strands and parallels in the film, such as the destructive consequences of late capitalism, neoliberal economic policies, and the consequential climate crisis. During weeklong rains Gerlachs farmlands are flooded, creating visionary images that foresee the moment the Netherlands will lose the struggle against the rising sea levels. This makes it her most contemporary political film too.

But there would be no room for all those observations if the film, like all her works, didn't create contemplative spaces, and took uninterrupted time to look at details, to roam around, amongst peripherals and ephemera. To focus on Gerlach's hands, that rub the grains from a young wheat ear to see if they are already ripe or thoughtfully stir the soil. His world unfolds in a grain of sand. Likewise, Van der Horsts artistic politics are always dispersed in a world of endless possibilities. And no matter how dark and traumatic the subject matters of her films, there are always moments of lightheartedness, of absurdity of humor. Without the absurdity of humor it is difficult to find emotion. The alternation of humor and gravity makes it bearable.

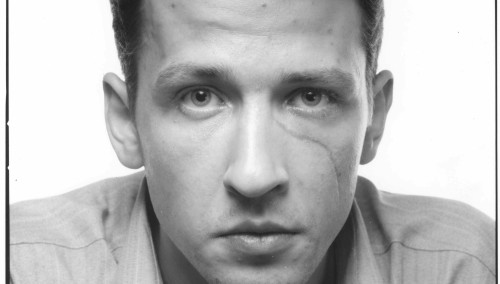

Just as Gerlach examines the sky and the earth and notes details that someone else would not see, Van der Horst looks at time and history. After the death of her father, she recently found a student film in which she interviews people about their first memories. It was perhaps the missing link to realize how important the themes of time, memory and recollection are in her works. In her first major film, a portrait of the Russian poet Boris Ryzhy (2008), who died young, she had nothing but vague black-and-white images and memories of his family and friends to build her film on. That and his words, that describe a time of transition. Of perestroika and chaos, of waking up from the socialist delusion into a reality of gangster capitalism, in which everyone who was not smart or fast enough to make it ended up in the cemetery. She patiently films all those grave portraits that are engraved like gray ghosts in the black marble gravestones. But she also uses her camera to study the faces of young men and women of the same age as Ryzhy when he ended his hopeless life in the steel scrap district of Yekaterinburg at the age of twenty-six, which he had snapped at and sung about in more than a thousand poems. It could have been her life had her Russian mother not met her Dutch father, and had she not grown up at another side of history.

She would also return to Russia for LOVE IS POTATOES (2017) and TURN YOUR BODY TO THE SUN (2021). In LOVE IS POTATOES she explores her own family history in the house where her mother grew up. There she finds letters and photos that testify to the dramatic events that the peasant family had to endure during the hard years under Lenin and Stalin. Black-and-white animations by Italian animator Simone Massi provide a symbolic commentary on everything the family kept silent about: fear and survival, disbelief, and propaganda. Her mother's remaining sisters have even suppressed the times of state-induced starvations. Displaced memories.

TURN YOUR BODY TO THE SUN explores another family history, that of writer Sana Valiulina, whose father first survived the Nazi POW camps and then was sent to Stalin's gulag. Here, too, letters and diaries give words to what was not spoken about: the taboo on the millions who lost their lives in captivity. Van der Horst complements these words with contaminated archive footage: military propaganda films that she slows down and zooms in on until they have been stripped of their original meaning. Until nothing but a final grain of film remains. The last microcosm of retention.

Aliona van der Horst's films are essayistic and classically documentary at the same time. They arise from thorough research and an observational way of working, often in close collaboration with others. For her first films, she worked extensively with camera person and editor Maasja Ooms, who received a co-direction credit for VOICES OF BAM (2006), shot on the debris of the earthquake that destroyed the Iranian city in 2003. When Van der Horst ended up on the regime's blacklist, Ooms returned to shoot the film, which they later put together in the montage to create an almost literary evocation. Van der Horst created the libretto for a choir of voices brings back what we no longer see: the absent lives of family members and loved ones.

Absence always conjures presence in her films by employing these kinds of artistic interventions. Often but not exclusively under repressive regimes, art is seen and experienced as a breeding ground and a safe haven for solace, reflection, and critical debate. For the excavation of the past and liberating perspectives on what it means to be a human. Through these artistic crossovers (don’t forget to listen to her films, as sound and music are always key) meditative spaces are created in which the speculative gives voice to the unspeakable. We also recognize this in WATER CHILDREN (2011), in which Van der Horst, together with Japanese pianist and performance artist Tomoko Mukaiyama, through cinematic performativity builds a cathedral of tens of thousands of almost translucent white silk dresses, tainted with menstrual blood. A memorial monument for the taboos surrounding menstruation, miscarriage, and menopause.

From BORIS RYZHY onwards a quote from the poet serves as a motto for her work: “Ugliness is beauty that cannot be contained within the soul.” It echoes other sentences, from other poets, from Francis Bacon and Edgar Allan Poe, who similarly said that “there is no beauty without strangeness,” or Rainer Maria Rilke, who described in his “Duino Elegies” how “beauty is nothing but the barely endurable onslaught of terror, which we admire so because it serenely disdains to destroy us.” Aliona van der Horst takes us beyond the scrap heaps of memory, takes the reflections of terrors that were and the terrors that could resurface again, and returns to the urgencies and resolutions of the present.

Dana Linssen is a film critic, philosopher, and writer from the Netherlands.