Working Worlds 2007

Along with “flexibility”, “mobility” is one of the characteristics required of employees in the globalised economy. Both terms are closely related: the decentralisation of industrial production and the service sector motivates movement across national boundaries, between continents, in real and in virtual space. This in turn demands a high degree of flexibility from the workers – teleworkers, entrepreneurs, industrial workers. Even though – in keeping with the paradigm of our era, of telecommunication and the World Wide Web – space is supposed to have shrunk and identity is no longer bound to locality, the effects of globalisation – in the sense of a permanent dislocation – are palpable in both professional and private ethics and thus also penetrable for the camera.

Working Worlds #4: Break and Depart shows five documentary film works this year, which deal with this gap between the local and the global, the absurdities and incompatibilities, and with the discovery of what is held in common, of an intercultural understanding, and a productive mingling of possible identities. The conditions are breaking up – in China and in Germany, in India and in the USA – and the people are departing: “Success stories” that always recognise – as the title of one of the films paradigmatically states – “losers” and “winners”, whose successes bear an element of loss just as their loss bears an element of nonsense and, not least of all, also a spark of comedy.

What all the works have in common cinematically is the moment of sympathetic observation, a view that is intimate, even if it is also stylising. The professional life, the working worlds of their protagonists, is consistently contrasted with the personal states, the imaginary, their individual and family identity constructions. Another motif is the filmic sense of the architectonic settings of the spaces of working and living, an interest in the imaginary potential that these kinds of places can have – here, there and everywhere. This is clearly anticipated by the diversity of locations and cultures represented by this year’s film programme. Bombay, Shanghai, Frankfurt, Theresienthal, Dortmund on the one side, the notion of the “whole world” (as market, as travel destination, as an incalculable, abstract magnitude) on the other.

On the other side of the globe, for example, we see the protagonists of JOHN & JANE – Indian call centre employees, advising and calming American consumers in laboriously acquired local US idiom, with imaginary names and in the right (wrong) time zone, while their home city of Bombay is fast asleep. Nearness and distance collapse, when the various “Johns” and “Janes” play America at night in suburban office complexes, returning at dawn to their neighbourhoods, which are changing just as subtly as the facial expressions, gestures and imagination of the teleworkers: futurism (and the science fiction like appearance of the call centre) is gradually encroaching into the city image of modern Mumbai through shopping malls, game halls and fast food restaurants.

The skilled workers shown in the German film DIE UNZERBRECHLICHEN are dislocated in a different way. For five hundred years glass has been processed into high quality products in the Bavarian town of Theresienthal, but for some years now the region has been an area of economic crisis and a large proportion of the glass-workers are unemployed. Enter the refurbishers: two consultants and a foundation put the rule to the test that it is possible to “break into” the global market specifically with local products, regional quality and a brand derived from a specific, evolved identity. The film observes – in the philanthropic gesture of documentary sympathy – how new productivity arises out of the cold stacks of the glass factory, how capital, a brand grows out of a cultural tradition. In this success story (the factory is revived and the spectre of unemployment is banished), the workers’ doubts and the efforts required to “re-invent” themselves are not lost.

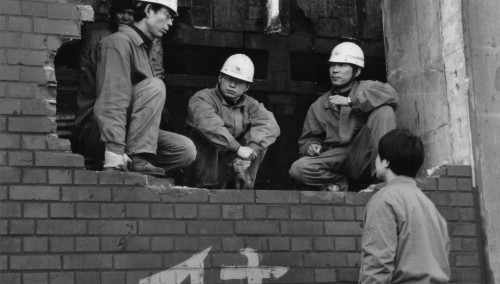

Also soon to be unemployed are the workers at the Kaiserstuhl coal plant near Dortmund. Their plant, once the pride of the region, has been closed and sold to a Chinese corporation, which is now dismantling it, piece by piece, to rebuild it in China as an exemplary plant. Actually, says one of the German workers in LOSERS AND WINNERS, the new owners are really only interested in the construction plans; yet under the suspicious eyes of the Germans, the Chinese demolition team, regarded as “intruders”, turns out to be a no less proud “working class”. “You are always just complaining and know everything better. We have already done this dozens of times and we can weld as well as you can!” snaps the Chinese foreman at his counterpart. In sequences reminiscent of JOHN & JANE, the filmmakers introduce China, culturally so different, to the “sleeping industrial giant” ironically as an almost extraterrestrial power: news from at home parallels the coal plant disassembly with the nation’s first manned space flight.

STUTTGART-SHANGHAI complements the former film by telling of a German couple that goes to China in “gold rush” manner to profit from the boom there. In the style of a docu-soap, the film sets the confrontation in the private sphere: whereas as the husband tries to follow in the footsteps of his father, who built up a flourishing textile business in a small Chinese city, the wife is less successful in adapting to the unfamiliar life in a foreign country. Talk of quick success and, in comparison with Europe, much better chances for wealth are dashed against a bourgeois notion of a happy family – the fact that the wife is pregnant and the sanitary facilities do not meet Western standards makes adaptation even more difficult. STUTTGARTSHANGHAI thus also shows an example of emigration under inverse conditions: even where an economic livelihood seems to be assured, the resistance to becoming accustomed to cultural practices is considerable and not compatible with the requirements of flexibility

Jan Peter’s miniature WIE ICH EIN FREIER REISEBEGLEITER WURDE concludes Working Worlds #4 as a polemic commentary especially on this demand for flexibility: while mysterious hoses dangle from the ceiling, the principle of self-initiative is demonstrated at the Frankfurt airport – a man in his mid-thirties, part of the generation of practical training, second jobs to be able to even finance job training, collecting bottles for a little money to supplement unemployment benefits, and a film director as a freelance tour guide. People look for and find/invent work – “Nothing but lonely self-entrepreneurs at a mouldy airport”.