Working Worlds 2013

The time of crises is far from over. This is a trivial platitude, as readjustments are evident everywhere, social upheavals are obvious, a sense of foreboding is omnipresent. Yet regardless of the origins of these changes and who benefits from them, they are taking place painfully slowly and are barely visible to the naked eye. And looking at E urope, it seems that everything is the same as it always has been. A few rebellions, demonstrations and strikes here and there, calls for reorientation in light of the growing financial crisis, none of them seem (yet) to seriously undermine faith in the rightness of the system. Social political life appears to carry on as ever, and the status quo is maintained as ever for the benefit of the same people as ever.

Roughly twenty years have passed since the call went out to everyone behind the Iron Curtain as well to take part in shaping the dream of freedom, to redeem the promise of greater prosperity – whatever this might mean in detail. Although this dream is, in fact, not yet over, freedom still turns out to be the exact opposite of a better life again and again. More freedom is announced in the same breath with the dismantling of welfare state measures, and workers’ rights are further reduced. Scandals become more frequent, and politically intended impoverishment is well under way.

Decision-makers are clearly fundamentally uninterested in taking care of basic things. A kind of high-level irresponsibility can be observed, the state continues to give the market free rein, and the market seems to remain the measure of all things.

From the privatization of public goods – drinking water is the most current example – all the way to the scandalous injustice that fulltime employment is no longer sufficient to cover the costs of living: this cannot go on. And yet it does.

The series “Working Worlds”, now in its tenth edition, sees itself as a collection of spotlights on the events at the periphery, on the failure of institutions, on the purportedly minor impacts from the dissolution of state and communal structures.

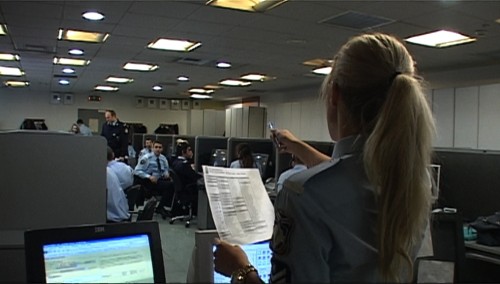

Work, and the conditions under which it is carried out, is always depicted in the selected films as a mirror of the social constitution of an entire country at the same time. One of them is the intimate kind of situation in Sofia’s Last Ambu lance, where a team and its ambulance lurch over the potholes of Sofia and through the decrepit health care system. Another is 1 0 0, where in a similarly constricted space, the men and women on the telephone of the emergency call center in Athens serve as a vent for everything going wrong in the country.

In To the Last Penny we meet those who cannot feed their family without state support, and the Graduates are faced with the sobering recognition that life outside the university has little to do with their ideals.

Finally, the short film We are the Mut ants looks into the employment severance machinery of a company that has taken restructuring measure to the extreme creating a parallel universe for its employees that cannot be fired.